The right rear tire blows out.

The car rolls more than 10 times in seven seconds. In those seven seconds, as he remembers, the scene flashes before his eyes.

Riding down the interstate in an SUV, John Clint Mabry, a senior college student, and his friends are on their way back to Baylor University after spring break. In seven seconds, his life changes.

Seven- the world starts spinning. Six— the metal crashes all around him. Five— part of his right leg flies out the car. Four— he waits for the last second of his life. Three— waiting. Two— still waiting. One— silence.

The car stops rolling. He waits for death, but it doesn’t come.

“Holy crap,” he remembers saying. “Get the heck out.”

He crawls out, goes back and forth to get his friends. Minutes pass, he sits at the side of the road and stares at the view— a torn SUV, a helicopter, ambulances, fire trucks. He sees his right leg damaged, mostly bone and flesh.

“I’m going to lose my leg,” he thought.

Having 14 surgeries didn’t change the outcome. A year after the accident, his doctor amputated his right leg below the knee. When he gazed at the vacancy where his leg used to be, “I felt like I’d never go back to normal,” he said.

He did, but it was a long road paved with drugs and alcohol.

Now, standing in front of college students, employees and TV cameras, John not only shares stories about his amputation, but also the turmoil followed by it— drug and alcohol, witnessing the death of a loved one, losing jobs, leaving his family and, finally, eventually, sobriety.

He wants the audience members to become what he is now— strong but not what he was then— weak.

After getting a prosthesis, John went skydiving, competed in triathlons and traveled to Japan and Brazil. He went to school and earned a rehabilitation counseling master’s degree at San Diego State University. Then, in 2004, he married his wife, Sarah Mabry, and moved to Los Angeles to pursue an acting career.

John from the outside had it all. He was a clean— cut, dashing young man. He had beautiful cars, a gorgeous, blonde wife and a nice condo in Los Angeles. He appeared in the movie, “Superbad,” with Jonah Hill and TV series “NCIS” and “Cold Case.”

He looked normal, but he wasn’t.

“Really on the inside, everything was a mess,” says Sarah. A few months after they got married, Sarah noticed something wrong. John missed phone calls, he avoided parties, he stayed up all night. And the wine didn’t last long in their house.

“I can hide it really well,” John said. He consumed 30 days of Adderall in just eight. He took piles of painkillers, sleeping pills, smoked marijuana outside when Sarah didn’t know and drank excessively.

He fuelled his body with substances to escape the anger rooted in his head. Behind the façade, John was a scared little child, shivering at a cold dark corner.

The truth sank in two years after their marriage. “It was shocking,” Sarah says. “I don’t even know my husband.”

In her memory, John was cool, macho.

Two days after meeting, John said he was going to marry her and take her to Europe.

“I was like, ‘No. No, you’re not’,” Sarah says. Sure enough, two years later, John changed Sarah’s last name before taking her abroad.

Growing up, John was always told to put on a happy face. He did, even when he lost his leg, even when his pain tortured him at night, even when he lost his only sibling, Matthew Mabry.

In 2008, John got a call from Matthew’s workplace saying he had not shown up. Driving down to his brother’s home, Sarah and John knew something was wrong. After kicking down Matthew’s door, John found him lying face down on the floor, cocaine on the table. He had been dead for three days.

At the time, Sarah worried Matthew’s death could have been John’s.

But John didn’t think so. “I’m not that bad,” he remembered thinking.

That was until his boss fired him for bringing his addiction to work. He went through rehab twice.

With a suddenly-absent husband and two crying sons confused about their father whereabouts, Sarah said she was mad, resentful and exhausted.

“When do I get to escape all these messes? I’m not the one who screwed up, but I’m the one who was paying all the consequences,” she questioned.

Her friends told her to divorce him.

She had wanted a divorce in 2005, the year after they got married. But her father told her to stay until she has done everything she could to save their marriage.

Seven years passed. The darkest days of their marriage came when John left home for those rehab stints. Sarah held the family tight.

A year and a half after the treatments, she found two red pills and couldn’t find the Breathalyzer which she used to keep John in check.

John relapsed, and Sarah gave up on their marriage.

It was 2013, they were married almost ten years, Sarah decided to divorce John. But fate intervened, Sarah discovered she was pregnant.

Instead of walking away, she brought her almost 1-year-old and 3-year-old to visit John in rehab and handed him a positive pregnancy test.

For Sarah, the family bond was inescapable.

In the last four years, John relapsed and went back into rehab. He thinks this time it works.

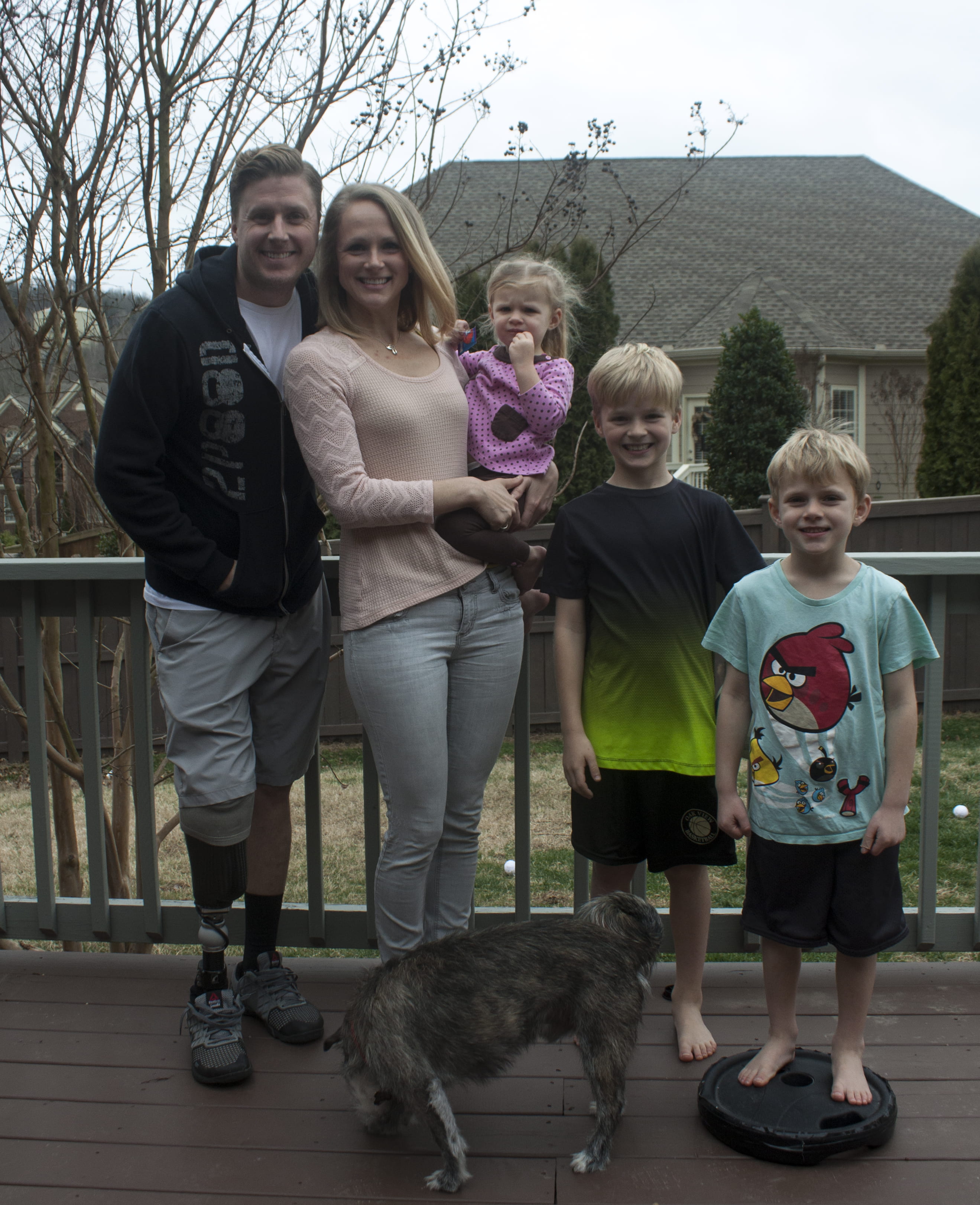

Today, at 39, John has been sober for more than a year. He works at Addiction Campuses, educating people about addiction. And Sarah is still married to him.

“Here I am. I am still here,” Sarah says. She is still here, beside John, hoping for his long-term sobriety.

“I am so lucky to have her,” John says. “Sometimes, I feel guilty that she suffered so much.”

The traumatic memories still hurt, but they no longer sabotage their life. Instead, they serve as fodder in John’s presentations of his brokenness and redemption. They also exist in Sarah’s blog where she encourages families battling with addiction.

More importantly, their stories play a vital role in teaching their children, to be not like their father was but who he is now.

View Mabry family blog: mabryliving.com

Published: April 3, 2017