“Sometimes things take too long to evolve. There are times when it’s necessary to move,” reasons a wise old man.

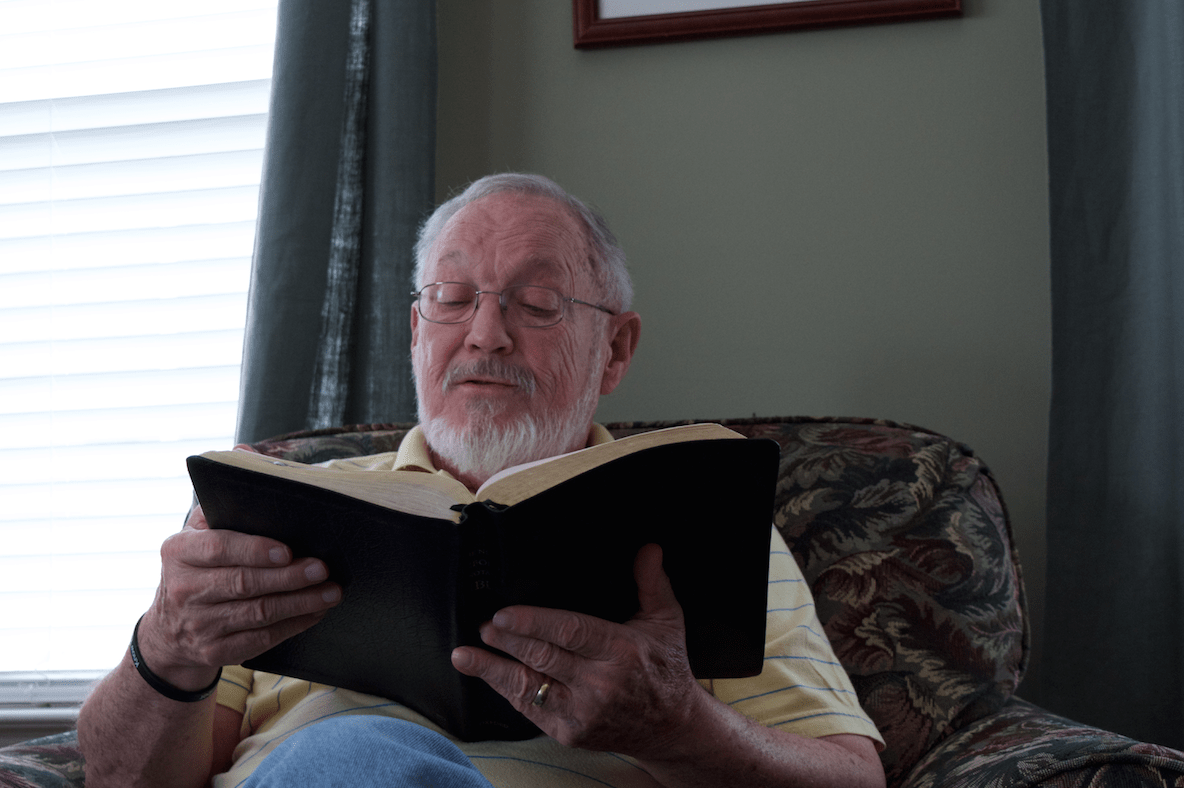

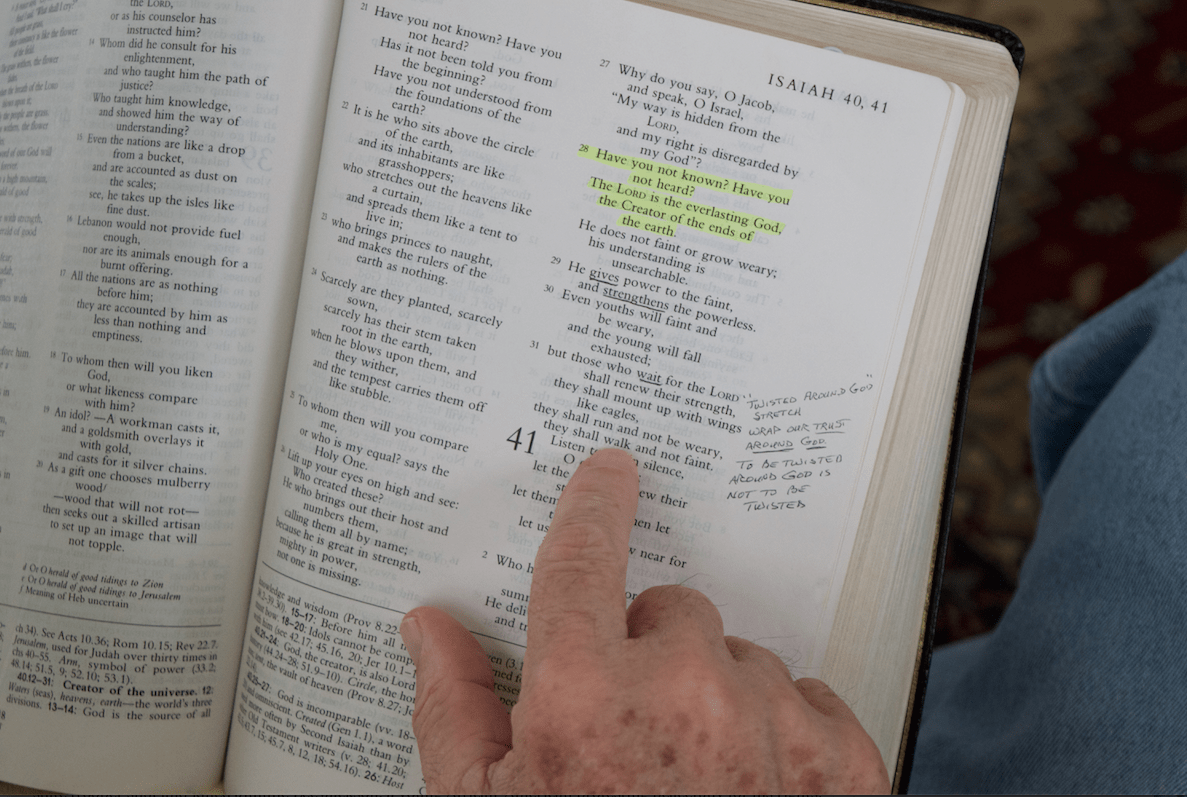

Lee Anglin, a retired American Baptist preacher, leans back in his chair, his hands folding over his lap after he sets down his well-worn, leather-bound Bible, and stares across the room as a small knowing smile plays across his face.

His bright blue eyes crinkle at the corners. His trim, wire glasses fall slightly to one side as his head tilts, reminiscing.

You can almost hear the footsteps echoing across his mind as he retraces the thousands of steps it took to march through history.

For a quiet sort of man, Anglin can tell you stories for hours.

Just a little over 50 years ago, back in 1965, a young, impassioned Anglin decided to drive to Selma, Alabama from Ontario, New York to fight for something he’d been fighting for his entire life, civil rights.

As a Caucasian man in his early 30s at the time, Anglin never personally felt the sting of civil injustice. But his entire entire life he witnessed the oppression of his African-American brothers and sisters.

“If you have something on your mind that’s wrong, you’re going to make waves,” shrugs Anglin.

Even though the Civil Rights Act just recently passed into law a year earlier, gray areas still existed in the interpretation of the law, especially in the South where racism still ran rampant.

In 1965, those still ruling with racism implemented loopholes like literacy tests to keep African-Americans from exercising the right to vote.

The civil rights leaders didn’t stand for it.

While the movement worked resolutely, yet quietly for a time, the tension came to a head when an Alabama state trooper shot and killed Jimmie Lee Jackson, a young African-American protesting peacefully for his rights.

The reaction was immediate.

And just a few weeks later, the first march on the state capital set off, but before they could cross county lines, the protestors were met with police batons and tear gas.

For Anglin and many others across the nation watching, the violence and injustice broadcast by the media during this march as well as a second attempt to march just a few days later left them incensed.

“There were some people who had not lived in or visited the South, and all their lives they had participated in voting. And they could not believe that there were people who were trying to stop us from registering to vote,” said civil rights leader Dr. Bernard Lafayette, an earlier organizer of the march.

“There were some people who had not lived in or visited the South, and all their lives they had participated in voting. And they could not believe that there were people who were trying to stop us from registering to vote,” said civil rights leader Dr. Bernard Lafayette, an earlier organizer of the march.

“They’d say this is America, we’re supposed to be different,” Lafayette recalled.

Lafayette spoke evenly, yet emphatically as if the sting of oppression felt like yesterday.

Anglin and Lafayette never met, but thousands of steps more than 50 years ago brought them and many others to stand together in the face of overwhelming oppression, intertwining the stories of thousands.

And for Anglin, he felt more than just anger and disgust. He saw it as a call to action.

A call to action that Anglin had been hearing for a long time, and it was finally time to answer.

A look of consternation flickers across his face, and he starts into a story about his best friend growing up.

His name was Hosea, Hosy for short. And Hosy was African-American.

Anglin didn’t even think of Hosy as being different. He didn’t think anything of the fact that people called him n-lover as a kid. Hosy was just Hosy, and he was his best friend.

Anglin didn’t understand the injustice of the situation until the two graduated high school. Even though Anglin grew up with little more to his name than Hosy, Anglin received the opportunity to go to Wake Forrest University. Hosy faced challenges finding a job.

“This happened all of my life where most of the African-Americans in my community didn’t stand a chance,” recalls Anglin.

“I just felt like I couldn’t make a difference, but maybe a movement like the march could help.”

So on Sunday, March 21, 1965, Anglin joined 3,200 fellow protestors on the 54-mile march, the final of three attempts, from Selma, Alabama to the state capital in Montgomery, Alabama.

And this time they marched right over that county line singing “We Shall Overcome.” And with the protection of U.S. Army troops and federalized Alabama National Guardsmen, under the orders of President Lyndon Johnson, the protestors made it to Montgomery five days later.

They fought for the right to march. And they marched for the right to vote.

However, even under the protection of the federal government, the march wasn’t all peaches and pralines.

Opponents of the march, or as Anglin calls them, young ruffians, would fain support for the march, then rush at marchers shouting and cursing.

“No matter if it’s just verbs and nouns, talking – it’s scary.”

But that didn’t hinder other peaceful protestors from joining all along the way.

“It started with local people standing on the side of the road watching us. They eventually decided to join the march, and we began to pick up more and more people on the way to Montgomery,” said Lafayette.

By the time the marchers reached Montgomery, Alabama, the crowd had grown to 25,000 people.

Although Anglin made it to Montgomery, he never did see the steps of that capital building.

But that didn’t matter to him.

“For me at least, Selma was the most important thing. Finally, I had investment or something enough to get there. I got there. That was a big deal,” says Anglin.

And he’s right. Later that August, President Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law.

“The first lesson as a nation is we should not let ourselves be easily divided,” said leading African-American heritage and culture proponent Dr. Reavis L. Mitchell, Jr., recalling the march and its legacy.

“Simply because something is a part of history, simply because things take place in the past such as racial injustice, political injustice, abuse of women – you can’t just leave it there. Those in charge have the responsibility to bring about change. The only thing constant is change,” Mitchell said.

And if you ask Anglin, he’ll tell you there will always be some sort of injustice in the world. But as he leans back in that comfy, old chair and starts leafing through that well-loved, leather Bible, he’ll also tell you, sometimes you just have to believe in the cause enough to show up.