The library nestles next to the Davidson County Clerk’s office, in a building with green awnings that blends into the foliage around it.

Inside, it’s a state building. Cinderblock walls. Static carpet. Orange wooden furniture.

People often wander in on accident. Thinking the space an extension of the clerk’s office, they ignore the letters on the door—“Nashville Talking Library,” —said volunteer Marilynn Trimble, who spends her Thursdays and Fridays at the front desk.

Then they ignore the lit sign in the foyer—“On Air”—, only to be directed back out and a few feet to the right by Trimble or another of the ladies who keeps watch over the door.

Illuminated by large windows, the space busies itself with island-like grey cubicles and long shelves stacked with reading material: books, magazines, newspapers. Each piece of literature moves frequently, different shelves denoting different stages in the reading process, from to-be-reads to those finished, in preparation for snail-mail shipping back to the main library.

Glass-doored recording booths line the perimeter, each equipped with a microphone and computer monitor for volunteers who lend their voices to the show, most in 58-minute episodes once per week.

Yet, beyond the buzzing hum of the radio from the front desk and the whispering rustle of Trimble’s embroidery, a hush hangs over the office.

Appropriate for a library.

Ironic for a talking library.

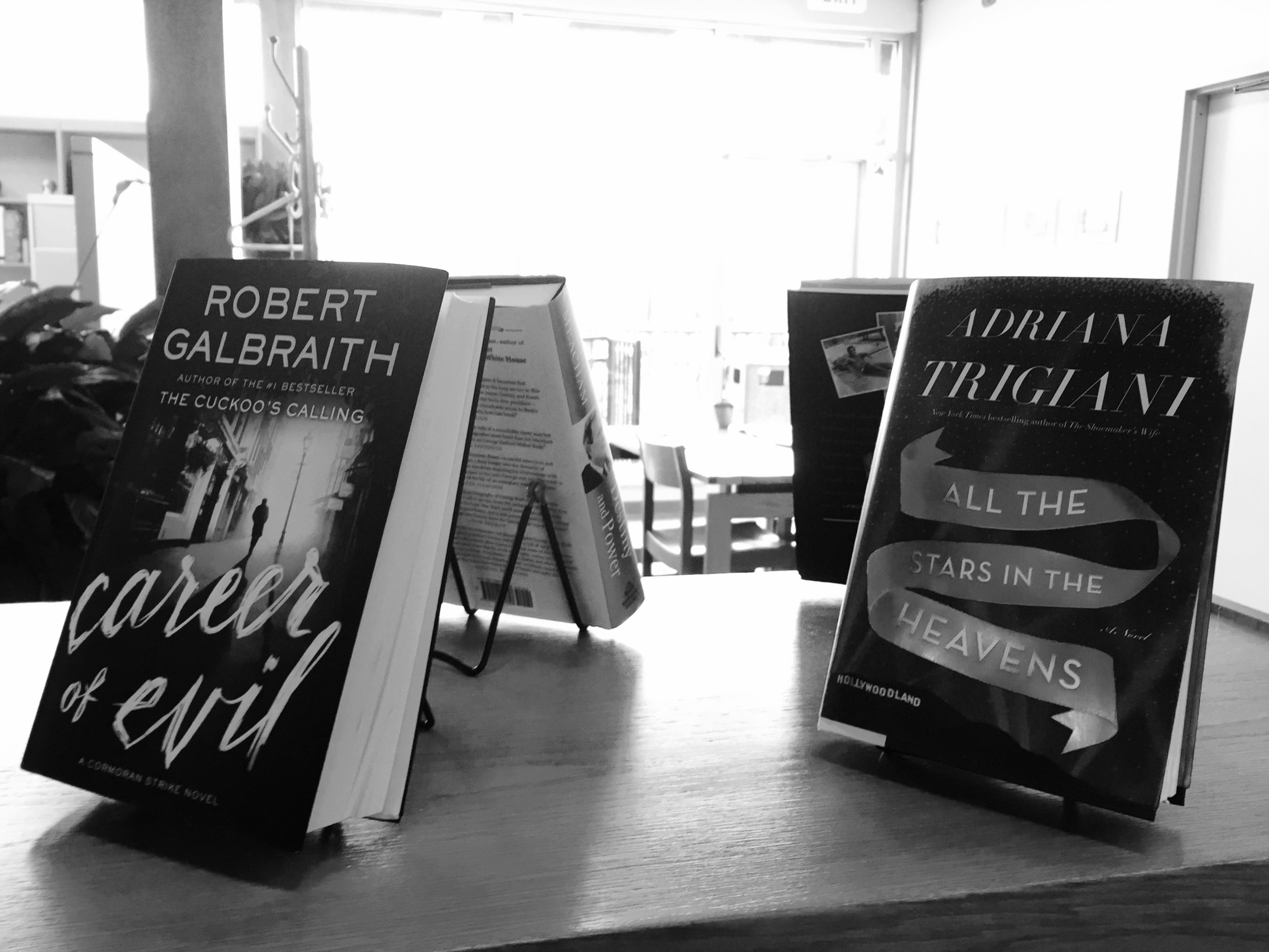

The Nashville Talking Library serves the metropolitan area as a radio broadcast service dedicated to spreading informative and entertaining literature to the blind and sight-impaired, those who cannot read it for themselves. Every day, for 24 hours a day, the library broadcasts volunteers reading aloud from published materials. The Nashville Scene. The Washington Times. Bestselling novels fresh off the library shelves.

“They have people to read anything. The Bible, Plato’s Republic, anything,” Trimble said, looking up from her sticky-note-strone post at the case of just-read books at the office’s entrance.

Volunteers record each work whole— often several episodes— weeks before it goes on air for the public.

Only those who read the daily edition of The Tennessean can be found live in the studio every morning, recorded in the studio at the building’s heart.

Because the talking library caters to a specifically hard of hearing listenership that relies on its services, the broadcast can avoid copyright costs and air whole books, recorded weeks in advance, said director Michael Wagner.

Volunteer Shelley Gotterer self-identifies as a “storyteller” and a “teaching artist.”

She used to teach English and drama, but now pulls double-duty, bringing folk stories to life on her show “World Tales” and serving as president of Friends of the Talking Library– a group dedicated to finding new listeners, started in 2013 when concerns were raised about the broadcast’s viability.

She recorded about 50 programs last year alone, she said. And she does it to connect people to a community from which they might otherwise feel isolated.

“Access to expensive electronic devices is often limited. A severe tremor makes using an iPad impossible. New novels, interesting ideas, relaxing entertainment, mild exercise programs, humor and local news can help keep the world of the mind and spirit open,” she said.

Reaching up to 4,000 people in Davidson and Williamson counties, the station’s broadcast piggybacks off the Nashville public radio signal, but can only be picked up with a special receiver tuned to the frequency: a box provided by the talking library to those who can prove their need. For some, that comes in the form of a submitted application with a counsellor verification. For others, the receiver comes as a complementary part of a visit to a local hospital or nursing home.

Naturally, the city’s older citizens make up the largest percentage of listenership, and the popularity of certain programming shows it.

“Ronald ‘Ronnie’ Qu– of Whites Creek, Tennessee…” a female volunteer’s even voice hummed gently from the receiver, interspersed with soft static. “Visitation will be 10 a.m. until 12–”

The readers love to hear the obituaries, Wagner said. They listen for familiar names.

The receivers themselves swiftly approach nostalgia in appearance. They look like mid-19th century radios, wooden boxes with a single dial for volume, two ports and an antenna. Made for user simplicity.

Over 600 receivers currently circulate among applicants, but Wagner says even these may end up defunct in the next few years, as plans for a password-protected streaming service go into development. It would open a whole new era for the service, also allowing it to provide a podcast-like service for easy access to older episodes of content.

For 15 years, the Nashville Talking Library has broadcast out of its little corner of Madison, Tennessee.

But little by little, the library makes plans for a different future in a different space, led by the people who have loved it most.

Wagner himself has thinning brown hair and a quiet demeanor.

He has worked at the talking library for 16 years. He started in 2000, back when the talking library— recently turned 25 years old— lived in the Howard School Building on Second Avenue. Before taking a position with the talking library, he spent time working at the main branch of the public library coordinating student volunteers; the job well-prepared him for the lateral move to the talking library.

“We used to have a gentleman who worked for us named Earnest Manning. He was blind. Born blind. He was our announcer, and I worked with him a number of years. I’d not been around blind people before, visually-impaired people. It was enlightening,” Wagner said.

He never worked in radio until he took the position, never did any recording work. He worked his way up through the project step-by-step.

When he hits the doors in the morning, his main goal: keeping the station on track for the day. Then getting a head start on making sure it stays on track tomorrow, too.

“We’re a radio station that’s on the air 24/7, and I just have to make sure the program is going well. If there’s anything that’s going to interfere with what our listeners are hearing, then we have to take care of it on this end, and it goes out from there,” he said.

Some days the job description means coordinating programs with the library’s parent organization, the International Association of Audio Information Services; others, it means subbing in for two straight hours of reading the news on a live broadcast.

When the upcoming move comes up in conversation, he grins; when he talks about it, he builds the new space downtown with his hands as much as he does with words.

Soon, the program will become a physical part of the equal access department of the Nashville Public Library’s main branch. The third floor of the looming downtown building, shared with the Library Services for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing, will house the recording booths, while the second will hold the main studio and control room, Wagner said.

For right now, headquartering so far outside of the city’s center has its pros and cons for the talking library. The library’s current location lends itself to a new set of volunteers— about 75 of them, Wagner said.

But buffeted by 18-wheelers and littered with construction, the 10 miles of interstate between the Nashville Talking Library and the Nashville Public Library’s main branch seem neither easy nor pleasant. Some prefer not to make the drive.

“It’s kind of out of sight out of mind, you know? A lot of people call and assume we’re part of the downtown library, so it just makes sense to do that,” Wagner said.

Construction will begin in March on the new space, which will overlook the west part of the city.

“It feels like we’re coming home again,” Wagner said.