May 1, 2016

For years, members of Nashville’s homeless population have sought solace in the woods of Fort Negley, the Civil War fort turned public park.

Tucked away between I-65, I-40 and a CSX rail line, the property’s northernmost hill hosts a quiet web of campsites spread out over two acres in an undeveloped area of the park.

The encampment is out of sight from both the roads and the park greenway, and for years it was out of mind as well. But now, its days are numbered.

When Mayor Megan Barry announced Metro officials would begin enforcing laws forbidding camping at Fort Negley, homeless advocates and Metro social service workers tried to find the residents alternative living situations, but as the deadline approached about two dozen people still occupied the camp.

At least two men couldn’t find a location that would allow them to keep pets. For the couples living at Fort Negley, going to a shelter would force them to live separately. Some men could not go to mission because of their history there.

Most of those who left the park have not secured permanent housing, but rather packed up and moved to another of the 200 known homeless camps in Davidson County.

Steve Hall has only been homeless for six months, and the last four he’s lived at Fort Negley. In his time there, Hall built a deck for his tent and mattress and tables for his portable stove and other belongings, planted a small garden, established a bird sanctuary and laid stonework in a shower area.

“It took me probably two months to find everything, but once I did and I knew what the design was, it came together rather quickly,” Hall said. “But it would’ve been much better.”

Hall’s plans for an extending his covered area and Japanese garden died with the news Metro would begin enforcing the ban on overnight camping. And this time, they meant it.

ROUND TWO

In December 2014, Metro officials began working with homeless advocates and the residents of Fort Negley to seek alternative options to encampments on Metro Parks property.

September 15, 2015 was the original deadline set during former Mayor Karl Dean’s tenure, but once Barry entered the mayor’s office, she granted the requests of homeless advocates allowing more time for those living at Fort Negley to find other solutions.

Seven months later, it’s go time.

The statement the mayor issued detailing the camp’s closure lists “efforts to implement the Fort Negley Master Plan and create an outdoor classroom for the Adventure Science Center” along with health and safety concerns as reasons for closing the encampment.

The release also said that in the past six months the police have been called 140 times and filed 21 incident reports, including two for aggravated assaults, one for rape and one for attempted rape.

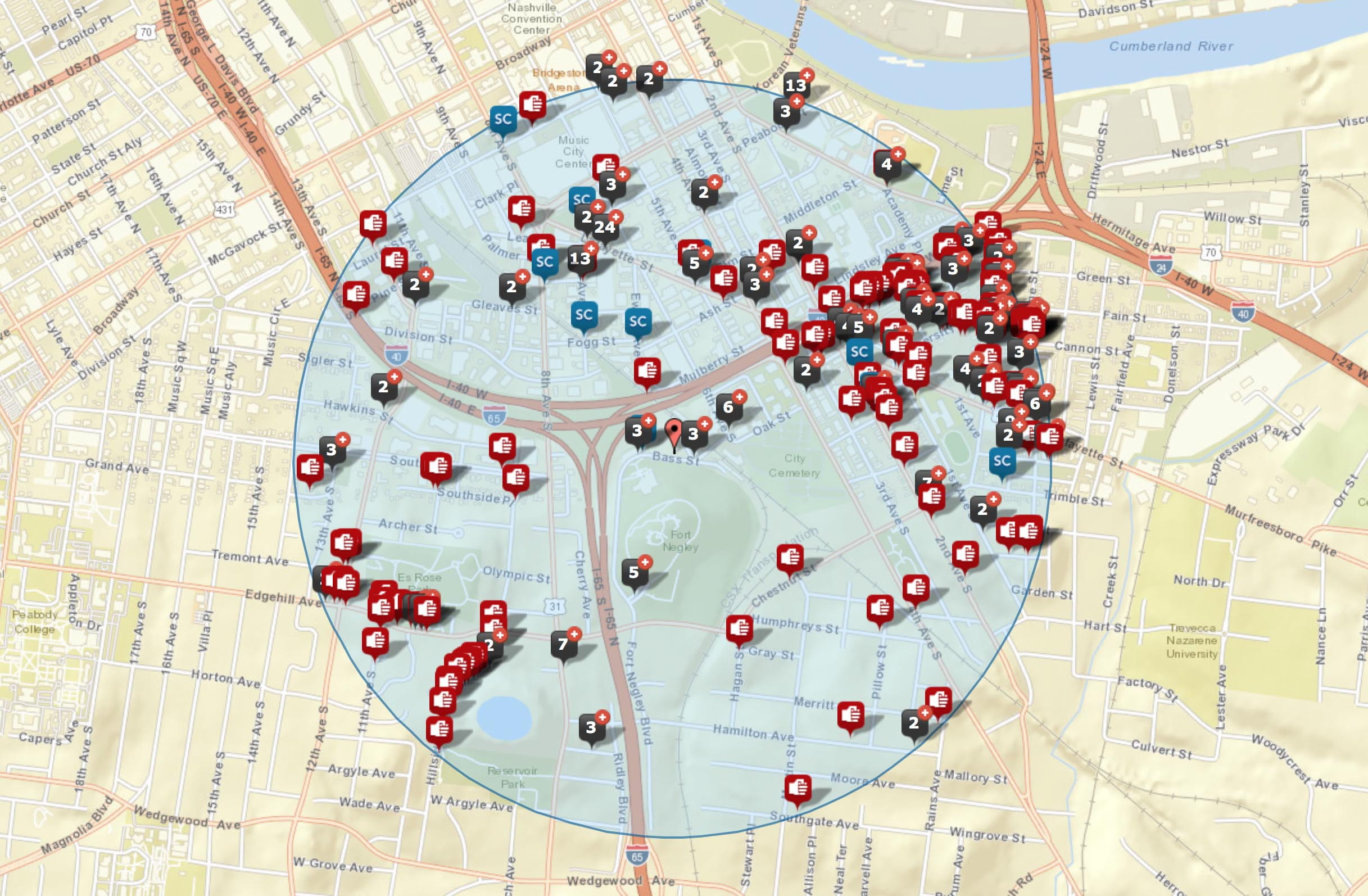

However, when compared to other areas within a mile from the encampment, crime statistics point to a different suggestion about the safety at Fort Negley. Reports of violent crime at Fort Negley are less dense during the six-month time period than areas including public housing at Sudekum Apartments, the Nashville Rescue Mission and the fringe of the Edgehill neighborhood.

Map shows all reported assaults and sex crimes within a one-mile radius of the Fort Negley encampment from October 24, 2015 – April 15, 2016. (Metro Nashville Police / CrimeMapping.com)

THE RALLY

The night of the April 15 deadline, homeless advocates organized by Open Table Nashville rallied at Public Square Park to demand more time for those still needing help and land allocated for encampments. The crowd swelled to around 200 people.

Homeless advocate Lindsey Krinks spends her days among the homeless, helping them manage pressure from city officials and work with social service providers to present options for the homeless.

“We’re here because we’re tied of spending all our time fighting for basic human rights like the right for housing, shelter and dignity,” Krinks said. “We want to move on and fight for better things, not just the basics. We’re tired of that.”

At dusk, just as thousands of honky tonkers, tourists and other patrons shuffled into the streets of downtown Nashville, the protesters began to march the 1.6 miles from the courthouse lawn to Fort Negley.

Homeless advocates march to end the criminalization of homelessness. April 15, 2016.

Proclamations of “homelessness is not a crime” reverberated along the Second Avenue corridor.

Most onlookers stopped and watched the display for a few moments. Some teenage girls whipped out their iPhones to Snapchat the unexpected spectacle.

But at least one homeless woman sitting on the sidewalk, upon learning the reason for the ruckus, abandoned her post and joined the march.

With 75 protesters marching his way, Metro Parks Director Tommy Lynch stood outside of the two-acre encampment that has drawn more public interest than any of the other 15,871 acres under his direction.

When the marchers arrive they are greeted by a handful of other homeless advocates, park officials and police. With three hours remaining until the enforcement begins, all that’s left to do is wait.

Homeless advocates and members of the community at Fort Negley pose for a photo shortly after the 11:oo p.m. deadline to evacuate the park. April 15, 2016.

THE HOUSING PROBLEM

In the statement regarding the enforcement of camping laws in Metro Parks, Barry said, “We believe that safe, alternative solutions have been identified to address the needs of the population that has been identified as living at Fort Negley.”

However, even with high priority placed on relocating the homeless at Fort Negley, securing housing is still an arduous process.

The first step in securing housing is submitting a pre-application to be added to the Metropolitan Development and Housing Agency’s Section 8 waiting list. Applications are only accepted during certain intervals throughout the year. The process for obtaining a voucher usually takes around two weeks.

Because of the urgency to remove the Fort Negley residents from Metro Property, several received expedited vouchers, thus placing them in front of homeless in other situations.

After acquiring a voucher, a person must apply and be approved for housing at a property meeting U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development standards. A person can only use the voucher for a certain period of time until it expires. If the voucher expires or the person is turned down for housing, the process starts anew.

By the time of the camping deadline, Tim Swanger and Cindy Leaf were the only couple with a voucher in hand. One individual with a voucher had already relocated. For the others, all available alternatives would be a downgrade from their living conditions at Fort Negley.

There is no designated land in Davidson County for homeless encampments.

Metro negotiated with Green Street Church of Christ to allow for ten campers to move the the church, and the already dense area designated for the homeless is now bursting at the seams. Based on GPS data, the area for camping at Green Street Church is less than one-fifth an acre.

For some of the established residents, the word homeless is almost overkill. “Houseless” is more appropriate. Stacked stone fire pits and mulched trails indicate the site was developed with cared for with pride.

Nearly every campsite is elevated on a wooden deck engineered to provide a flat, elevated surface for a tent. Tarps rigged to trees around the deck extend protection from the sun and rain.

At one site, dubbed Far Point Station, a continuous stretch of awning covers three elevated six-person tents. The 10-foot beam supporting the awning gives the covering a semicircular shape, almost like a plastic quonset hut.

Despite their advanced development, the campsites were on condemned land and the homeless knew they had to move. What they didn’t know, however, was how soon and intense the pressure to get out would come.

THE CAPTAIN

“Captain” Chris Scott Fieselman isn’t from these parts. His Long Island accent stands out from the crowd’s chatter and his unmistakable laugh could cut through concrete.

“Land needs to be allocated for encampments,” Fieselman said. “Affordable housing is a great thing, a fantastic idea, but there’s a part of society that’s starting off below the affordable housing mark, like when they’ve got nothing… They need to start a little lower than that and that’s why tents are the only other option.”

Undeniably the most outspoken resident of the encampment, Fieselman has become the darling of local media. When Mayor Barry held interdepartmental meetings discussing Fort Negley, Fieselman was included in the conversations as a representative from the encampment.

Fieselman has lived at Fort Negley off and on for the past seven years, and it’s not laziness or misfortune that keeps Fieselman sticking around but rather his thirst for helping other homeless people.

With Fieselman as its spokesman, the community achieved getting trash pickup twice a week.

And for the dirtier business, “We do it with five-gallon buckets and liners and we change them out once a week. So we’re not crapping in the woods,” Fieselman said. “We’ve learned a lot.”

Fieselman draws on skills acquired while serving in the Korean War to better the living conditions at Fort Negley.

“This is a form of military installation,” Fieselman said. “I can’t think of a better place for me to be.”

Fieselman didn’t participate in the rally or the march.

“Someone’s got to hold down the fort,” he said.

Once the march arrived at the fort, Fieselman was in his element chatting up fresh ears.

“Many people have gotten jobs, gotten together and gotten out of here,” Fieselman said. “That’s what we commonly call success. That’s what we’re doing here. Success. People are getting it.”

Steve Hall, the man with the bird sanctuary and stone shower area, is Fieselman’s case in point.

Hall had worked as a quality control inspector for 25 years before changing careers to work as an electrician in 1999.

In 2013, a perforated ulcer hospitalized him for 13 days. Without insurance, Hall walked out of the hospital with a $136,000 bill. Even with help from his brother, Hall ended up on the streets.

The morning after the camping law enforcement began, Hall packed up the last of his belongings with a calm and collected demeanor.

“The buttercups didn’t even come out yet,” Hall sighed as he looked down at the small garden he prepared to leave behind.

With the help of Open Table Nashville, Hall was set to move to a smaller, isolated campsite close to town and his new job in electrical maintenance at some of downtown Nashville’s most popular attractions.

“I hope it’ll be comfortable for a little while until I find some housing. Work a few weeks, get some paychecks saved up and then find housing somewhere,” Hall said. “I have to, because I can’t be going into work without a shower and cleaning up.”

ENFORCEMENT

As Hall moved out, Metro officials continued moving in.

Starting just after midnight Saturday, Metro Park Police began its nightly rounds of the campsite. Sunday night, police cited six people sleeping at Fort Negley. Every night since Friday, the police have walked through between 11 p.m. and 1 a.m. and checked each tent, taking the names and asking if they have made contact with Metro Social Services.

After four nights of wake up calls from police, the remaining residents at Fort Negley had a new stressor to deal with.

On Tuesday, Bobcat operators began clearing the brush around the campsite, coming within inches of demolishing one tent and deck before someone was able to inform the operator the entire area was not yet clear of human life.

Bobcats cleared the brush around the homeless camp. April 19, 2016.

By Thursday, chainsaws had cut down forsaken decks and all abandoned property had been removed.

For Tim Swanger and Cindy Leaf, who have a Section 8 voucher but no housing to move into for another two months, Metro’s reclamation of the encampment appears more aggressive than the “compassionate, service-oriented approach” the mayor’s statement described.

Other than stating “efforts to implement the Fort Negley Master Plan and create an outdoor classroom for the Adventure Science Center,” Metro has not elaborated on any specific uses for the land.

Efforts to speak with Metro officials about specific plans for the property were directed to the mayor’s press secretary, Sean Braisted, who did not answer nor return emails and phone calls.

“Wow. She wasn’t kidding. She was not kidding,” Swanger mumbled as he overlooked a barren area that previously held nine large tents. “You would never even know there were tents there if it wasn’t for the leaves.”

Tim Swanger surveys an area known to the homeless community as “The Gulch” after five large tents wree cleared from the grounds. April 21, 2016.

Further up the Hill, “Captain” Chris Fieselman decided to read the book of Job.

“Here’s the good part. ‘Naked I came from my mother’s womb. Naked shall I return there. The Lord gave and the Lord has taken away. Blessed be the name of the Lord!’ That’s the one I needed to read right now,” Fieselman said as the spring rain started to pitter patter on the tarp covering his friend’s deck.

“Captain” Chris Scott Fieselman reads the book of Job after the decks at Fort Negley were demolished. April 21, 2016.

What’s left of his deck is at the bottom of the hill in the blue dumpster.

“I’ll probably never sit at the mayor’s table again. Once she gets me out of here I’m no longer a stakeholder. Cause there’s nothing at stake. They win.”

“Did I ask for too much?” Fieselman wonders aloud. “It’s a little piece of property they didn’t give a damn about for how long? Decades. Now all of a sudden it’s the hottest piece of property in Nashville.”

For the charismatic symbol of the Fort Negley homeless encampment, reality hit hard.

“Thought I had a prototype. Turns out, I had a pain in the ass of the city of Nashville.”