I bring my car to nearly a full stop before turning in, pulling in behind an older Lexus sedan. I sit. Confused and idling in the driveway, an ordinary brick house accented by a tidy porch, settled in a residential neighborhood stands in front of me. I cut the engine. A young couple pushing a stroller and walking their two dogs passes by.

Surely, I have driven to the wrong house. I sit waiting for a response. One minute passes, two. I open my car door and then I can hear it, leading me down the driveway and around the side of the house.

“Sorry, I followed the music,” I apologize, nearly walking into the guy sitting on the pavement behind the house fixing a broken basketball hoop five years past its prime.

Unusually warm for a Sunday in January, the men have taken their weekend antics to the backyard.

“Yo! You made it!” Blake Mankin stands at the edge of an elevated wooden deck, a beat pulses through his amp, his arms spread wide open. I climb the deck stairs before he turns back to continue freestyle rapping the final verse to a beat with a friend.

Cutting off the music, Blake, the front man of “Mr. B and The Tribal Hoose” welcomes me to his home. The “Hoose,” – which doubles as an expression for both his house and the all-inclusive group of people who surround him – is a ranch-colonial crossover which his mother helped him find in suburban Nashville. Currently it serves as residence and recording studio. Having only met once, days before, he treats me like he would a friend – periodically breaking out into rap, urging me to step up for a verse. I am in his Hoose now.

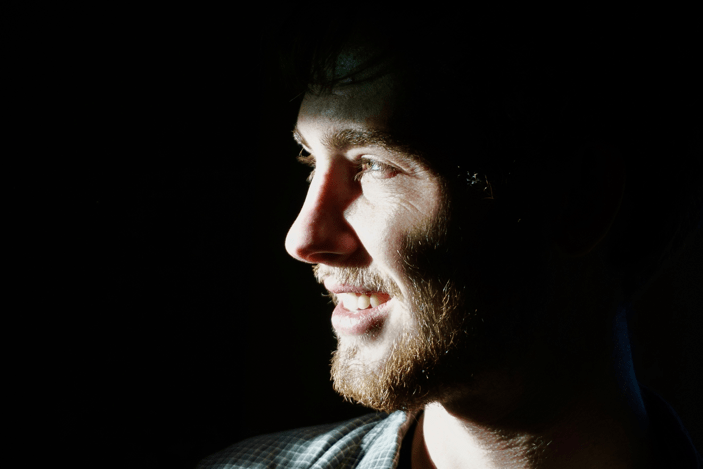

We pause. Freckles dot Blake’s face between patches of rusted blonde scruff, flashing a wide smile he pulls me in for a hug. Blake is a hugger.

—

A recent Belmont University alumni, Blake has transitioned from full-time student to full-time rapper and part-time app creator. The launch of his mobile app “Mr. B’s Rap App” which encourages confidence and creativity through the education of freestyle rap has played an instrumental role in what he calls his “human experience.”

The app, which boasts a bank of beats allows users to create an assisted freestyle rap through a changing list of suggested rhyming phrases displayed on the screen. Blake developed the app after a college professor suggested he take his original idea, a book of rhyming phrases aimed at rappers, down the digital route.

I met Blake for the first time just a few days earlier in the crowded café Frothy Monkey, where Blake explained why he created his app.

A self-described unengaged student, nothing about a traditional classroom setting held Blake’s attention, which lead him to wonder if the things he was passionate about, like the rap app, could be adapted to the classroom.

“The best way to complain is to make things,” he said.

While out at a restaurant in his home town of Scottsdale, Arizona, Blake ran into an old elementary school teacher, Heidi Gledhill. The two struck up a conversation, and Blake lamenting on his college experience showed her the app. He wondered how children would react to it – prompting Gledhill to invite him to try it out with her students.

Blake visited the classroom twice, most recently in January where the students incorporated their vocabulary words into the app. Their positive reaction energized him in a way that still resonates with him months later. Children who were quiet on any other day stood up in front of their peers and rapped, he explained. Almost the entire class took a turn, Blake says beaming with pride.

One child, Evan, had a natural talent for rap, he said. He spent much of the class time freestyling in front of his peers. Afterward, Gledhill pulled Blake and with tears in her eyes;

“She said ‘Blake that was incredible what you just did…Evan does not talk in class.’”

But Blake had a hunch that the app might help the children with their self-confidence. He said, that his inspiration for introducing the app in the classroom came from a study he’d researched presented by Dr. Charles Limb at Johns Hopkins University. Certain parts of the brain related to self-confidence and self-awareness are activated when you freestyle, and another part of the brain, linked to inhibitions and fears, is lowered according to his research.

Blake used this information to pitch the app to other schools, highlighting the importance of practiced self-confidence.

—

Blake settles back out on the driveway after giving me a “Hoose” tour while wearing fur-lined jacket and toting a roll-around amp.

Blake is rarely at rest. Taking a moment to sit, he climbs on the back of a Chevy Impala, Nathan Fouts, known by his stage name “Littlefoot” and Ian Munsick, a member of the Tribal Hoose stand near him at the foot of the car. Like their sun, his “Hoose” always seems to be in his orbit.

“Blake will make you feel real uncomfortable in public,” jokes Munsick, breaking away to retire the broken basketball hoop to the garage and with Blake out of ear shot. Littlefoot hears Munsick poking fun and the men laugh, but underneath lays an unspoken understanding that there is truth to the statement.

With his unconventional style and outgoing personality, Blake unwittingly draws attention to himself wherever he goes.

I witnessed this first-hand at the coffee shop.

—

Sitting at Frothy Monkey, he somberly tells me about using music as an outlet for his emotional pain, his tone in contrast to his usual sunny disposition.

“The only time I let it come to life is typically in my music. A lot of times people think my music is a direct reflection of me, which maybe it is, maybe that’s what is going on inside.”

Breaking out into rap, he spits a song called “2 Sad 2 Cry.”

An older gentleman in a suit monotonously tapping on a lap top turns to glare at us because Blake’s voice is now noticeably louder than the dull whisper of the coffee house. We would’ve gone otherwise unnoticed sitting back into the corner, but Blake, with his back towards most of the coffee shop, raps on.

He can’t feel the eyes of our neighbors burning into the back of his head. I can feel my face start to flush, avoiding the eyes of the man in the suit I look for refuge in the girl who hasn’t looked up once from her book since she sat down. My mistake. She glares back at me and my palms start to sweat. Blake doesn’t notice, or maybe he just doesn’t care.

The song speaks directly to his inner demons.

I feel like I’m losing my colorful personality.

Feel like everyone now wants something out of me.

I feel like I’m even doubting myself

But I’m too damned depressed to seek out any type of help.

Rapping through the chorus he finishes and sits quietly for the first time in half an hour. Then erupts into a fit of laughter.

“Part of me feels like, I feel like, this is terrible, the things I say, I really do feel that. I just won’t ever say it to somebody’s face. It comes off a little too strong, so when I put it in my music it is not quite as direct,” he said, in a rare moment of spoken honesty.

—

Sitting in the café, Blake rambles again, desperately trying to fill the empty space left over from his momentary confessional. The man in the suit has returned to typing, and the girl appears lost in her book. It’s just me and Blake, again.

Then he pauses in response to my question, just for a moment I’m afraid I’ve offended him before he answers. His biggest regret is not being able to stay sober.

“I’m really curious what extended sobriety would be like for me…It’s a crutch, it’s a copout,” says Blake while playing with the label of a water bottle.

He said he’s not had extended sobriety since he was 13, almost a decade.

“I hadn’t woken up too long ago, even coming over here, it was a temptation…before I came and I was like “‘no, have some part of your day sober.’”

Blake said he isn’t sober because in his head he can rationalize the substance abuse.

It’s his “fix.”

He says that he’s surrounded by creative types who abuse “real drugs,” like prescription pills. He thinks those bad habits from the people in his life don’t rub off on him he also says.

Every time he stays sober for a few days, he makes progress, both in his art and in his business, he says. But it is too hard to stop for good.

Peacocking through life, his affinity for being the most outrageous one in the room is smoke and mirrors for a kid with real inner demons. Blake’s lyrics expose personal struggle I could never grasp from just meeting him on the street.

“I just want to be honest, because I know people will be able to relate if I keep it human,” says Blake.

—

His interest in helping children find self-confidence in the classroom coincides with the struggles he still faces in his own life. While Blake uses rap as a means of self-expression now, he didn’t have the outlet as a student. He wants to be the person he needed growing up — a superhero, dressed in costume with a grand public persona.

—

The tribe winds down for the night, a gang of misfits standing in the glow of a fluorescent garage light.

I snap a picture; the boys take notice and Blake disappears into the garage.

Emerging some seconds later with a makeshift T-shirt flag and PVC pipe, I photograph Blake and his tribal hoose. Then I get in my car and watch him get smaller in the rear-view mirror.